How Threat Modeling Became the New Compliance Must-Have in FinTech

Table of Contents

Financial regulators are raising the bar on cybersecurity, expecting financial institutions to identify risks before code is written. New guidance from the FFIEC, NCUA, OCC, FTC, and NYDFS increasingly points to threat modeling and secure design reviews as essential parts of compliance. Examiners now want to see evidence that teams thought about threats early, documented design decisions, and aligned controls with real risks.

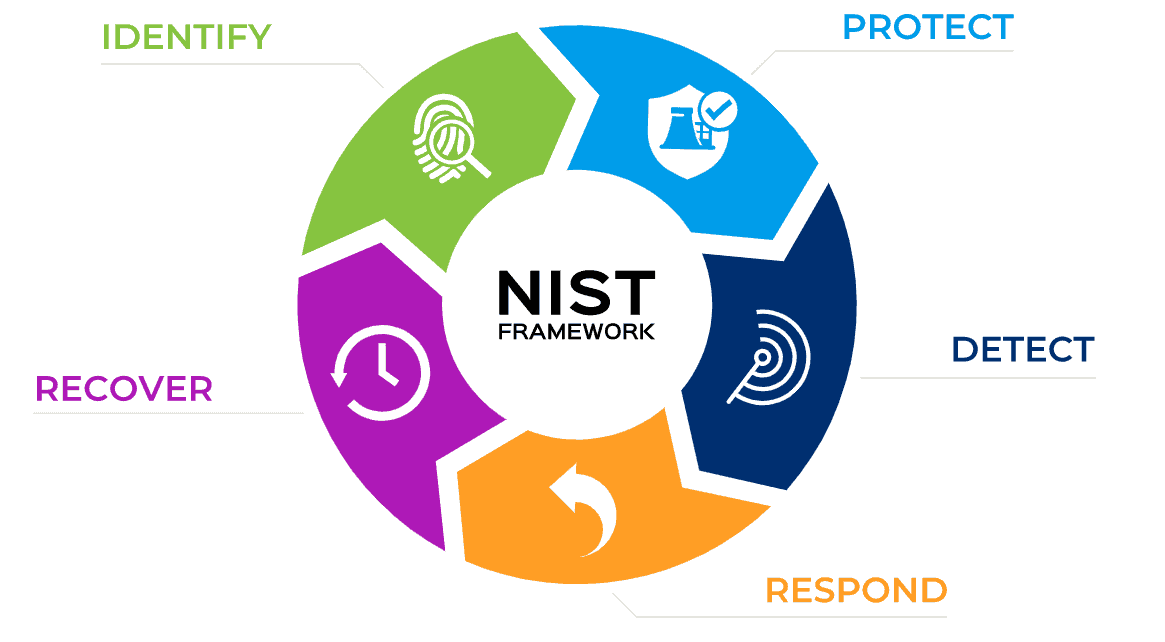

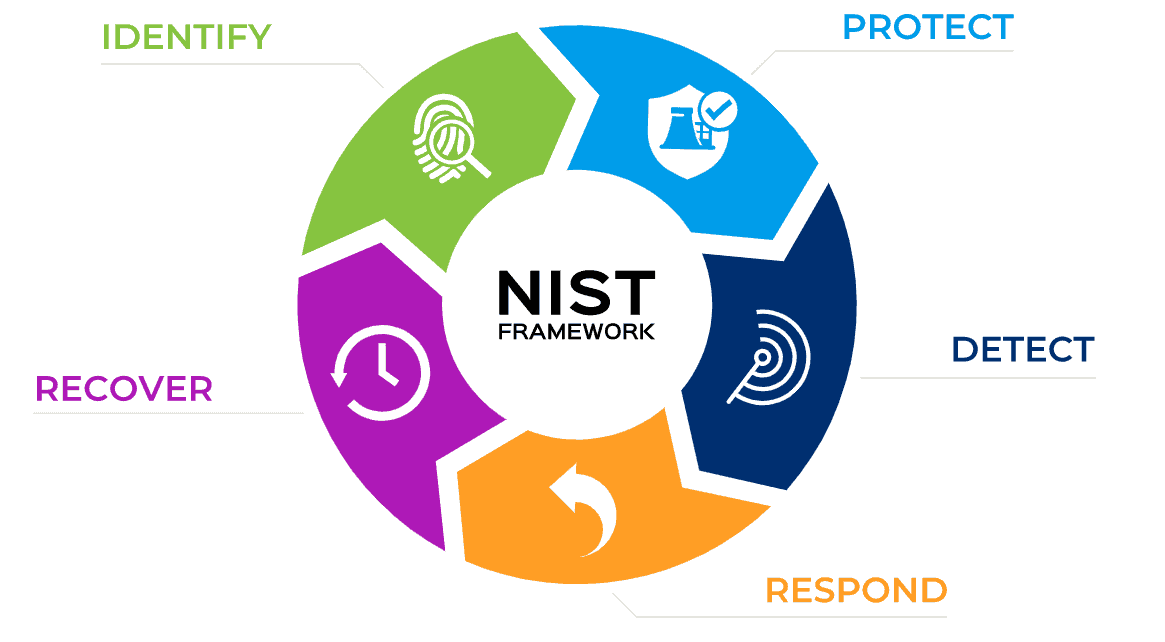

Regulators want to see secure design thinking built into how features are planned, not patched. For credit unions and banks, this means moving from reactive scanning to design-time risk analysis — understanding threats in architecture, vendor integrations, and third-party services. The retirement of the FFIEC Cybersecurity Assessment Tool underscores this shift toward industry-standard frameworks like NIST and CISA’s Secure-by-Design principles.

This article is a practical guide for security and GRC leaders in the financial sector on how to mitigate compliance risk by investing in secure design workflows.

1. Introduction: anticipating regulatory risk before code is written

How early does your security program get involved when you launch a new feature? In many organizations security steps in after development, running vulnerability scanners and penetration tests on software that is already in production. Regulators are nudging financial institutions to move left in the life cycle and think about security at design time, not just after deployment. The Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council (FFIEC), the National Credit Union Administration (NCUA) and standards bodies such as NIST are shifting expectations from reactive scanning toward design‑level risk analysis. Financial institutions are now expected to anticipate risks before incidents occur and to document why particular controls and architectures were selected. This article explains what threat modeling is, how industry guidance is signaling its importance and why credit unions should take notice.

FFIEC, NCUA, and NIST are shifting expectations from reactive scanning toward design‑level risk analysis.

2. What is threat modeling and why it matters

Threat modeling is a structured approach to identifying potential security and privacy threats at the design phase of a system, before a single line of code is written. It requires teams to enumerate assets, define trust boundaries and hypothesize how an adversary might misuse or compromise those assets. When performed early it helps organizations to:

- Anticipate risks: by brainstorming possible attack paths, institutions can address weaknesses in architecture before they become code defects.

- Validate architecture: diagrams and data‑flow models are reviewed to ensure that authentication, authorization and segregation of duties are applied appropriately.

- Align controls with real threats: instead of blindly implementing controls, threat modeling ties mitigation actions to specific attack vectors, making control selection defensible during audits.

- Support audit and compliance: documented threat models provide examiners with evidence that risks were considered and that controls were selected intentionally.

The need for threat identification is especially acute in complex environments built on APIs, cloud infrastructure and artificial‑intelligence models, where an insecure integration or misconfigured identity boundary can lead to catastrophic data breaches. Vendor integrations and third‑party services introduce additional attack surfaces that must be evaluated, and regulators increasingly expect institutions to demonstrate that they have analyzed these risks.

Regulators increasingly expect institutions to demonstrate that they have analyzed these risks.

3. How FFIEC is signaling the need for threat modeling

The FFIEC Information Security booklet, part of the IT Examination Handbook, explicitly calls for the use of threat modeling. The booklet states that institutions should demonstrate using threat modeling to understand the nature, frequency and sophistication of threats and use this knowledge to evaluate information‑security risks and adjust controls. The same booklet notes that threat‑analysis tools such as event trees, attack trees and kill chains help management deconstruct events and identify the most effective mitigation measures. In other words, FFIEC examiners expect more than a simple risk matrix; they look for structured techniques that tie threats to systems and controls.

FFIEC examiners expect more than a simple risk matrix; they look for structured techniques that tie threats to systems and controls.

Frameworks mandating or encouraging threat modeling and design reviews

The regulatory environment is also evolving. The FFIEC announced that it would sunset the Cybersecurity Assessment Tool (CAT) on August 31 2025. In its statement the Council explained that it would remove the CAT from its website and that it had decided not to update the CAT to incorporate new government resources such as NIST Cybersecurity Framework 2.0 and CISA’s Cybersecurity Performance Goals. The CAT has since been retired. Institutions are encouraged to refer directly to these frameworks and other standardized tools. The CAT has since been retired. Institutions are encouraged to refer directly to these frameworks and other standardized tools. This change underscores the move toward industry‑standard frameworks that emphasize early identification of risks, including secure design and software development practices.

The FFIEC’s Architecture, Infrastructure and Operations booklet further underscores design‑time risk evaluation. A Federal Reserve supervisory letter transmitting the booklet notes that it discusses processes for addressing risk related to the design and implementation of IT systems and principles to help examiners evaluate delivery of products and services. When examiners review a bank’s architecture they are looking for evidence that management has considered security risks during system design rather than bolting on controls after deployment.

When examiners review a bank’s architecture they are looking for evidence that management has considered security risks during system design rather than bolting on controls after deployment.

4. Where NCUA and credit‑union supervision are headed

Credit unions are examined under the same FFIEC guidance but also receive additional oversight from the NCUA. The NCUA uses a risk‑focused approach that evaluates management’s ability to recognize, assess, monitor and manage information systems and technology‑related risks. Examiners concentrate on areas of material risk relevant to the credit union’s size and business model.

The NCUA’s Information Security Examination (ISE) requirements provide more detail. In the CORE+ risk‑assessment component, the ISE states that credit unions must use threat modeling to better understand the nature, frequency and sophistication of threats. They must define inherent and residual risk ratings and measure risk using qualitative or quantitative methods. The requirements also call for maintaining a catalog of vulnerabilities, mapping threats to risks and updating risk assessments when technologies or services chang. These directives make threat identification an integral part of the risk‑assessment process for higher‑complexity credit unions.

These directives make threat modeling an integral part of the risk‑assessment process for higher‑complexity credit unions.

Looking ahead, the NCUA’s 2025 supervisory priorities keep cybersecurity at the top of the agenda. The agency notes that cyberattacks against credit unions and their vendors are becoming more frequent and sophisticated, and that examiners will continue to use information‑security examination procedures to assess whether credit unions have robust programs. The priorities emphasize the need for proactive management of information‑security programs and ongoing due diligence of critical service providers via continuous threat identification. This reinforces the expectation that credit unions must evaluate risks introduced by vendors and third‑party technology providers before incidents occur.

5. What these standards have in common

Across FFIEC, NCUA, NIST and OCC guidance there is a consistent message: security must start early and be documented.

- Early security engagement: Risk analysis should happen during system design. The AIO booklet talks about processes for addressing risk during design and implementation. The NCUA ISE requires threat modeling as part of the risk‑assessment process.

- Design documentation: Examiners expect to see architecture diagrams, data‑flow maps, attack trees and other artifacts that illustrate how systems work and where controls are applied. The FFIEC booklet recommends using threat‑analysis tools such as attack trees and kill chains to break down complex events and identify mitigation measures. The OCC’s Cybersecurity Supervision Work Program, aligned with the NIST Cybersecurity Framework, focuses on maintaining asset inventories and data‑flow diagrams and identifying external connections (information from the CSW attachment summarized in previous research).

- Justification for control choices: Threat models help management decide which controls are appropriate and why. The FFIEC emphasizes that threat modeling informs the selection of safeguards , and the NCUA ISE requires mapping vulnerabilities to threats and risk ratings.

- Vendor and service review: The NCUA’s 2025 priorities call for continuous due diligence of critical service providers. This means credit unions must evaluate the architecture and security practices of vendors and ensure that vendor integrations do not introduce unmanaged risks.

These common threads show that “scanning and patching” alone cannot satisfy examination expectations. Financial institutions must show that they have thought about threats up front, documented their findings and selected controls accordingly.

6. Threat Modeling’s Biggest Obstacles Today

Despite the clear guidance, many institutions still treat threat modeling as a manual, sporadic exercise. Effective modeling requires experienced security architects to facilitate workshops, draw diagrams and translate findings into actionable controls. In fast‑moving development environments this work often competes with feature deadlines and is postponed or omitted. As a result, design reviews happen late (if at all), leaving audit and compliance teams with little evidence that risks were considered. The resource and time burden of traditional threat modeling is one reason why automation is becoming attractive.

7. Looking ahead: regulators want to see secure design thinking

Financial regulators and examiners increasingly ask, “What is your process for evaluating risk before features go live?” Threat modeling and security design reviews provide the answer. They demonstrate that your institution has thought about how systems can be abused, selected controls based on that analysis and documented the rationale for examiners. As the FFIEC retires its legacy tools and NCUA examiners lean into structured risk assessments, security architecture becomes a compliance asset. In the next issue of this blog series we will explore how DevArmor automates threat modeling and design review, helping credit unions and community banks meet these expectations without slowing down development.

References

- FFIEC Information Technology Examination Handbook – Information Security booklet (2016). Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council. https://ithandbook.ffiec.gov/it-booklets/information-security/

- NCUA Information Security Examination (ISE) Requirements 2023 – CORE+ risk assessment. National Credit Union Administration / TraceSecurity. https://www.tracesecurity.com/uploads/NCUA-ISE-Requirements-2023.pdf

- NCUA’s Information Security Examination and Cybersecurity Assessment Program. National Credit Union Administration (risk‑focused exam overview). https://ncua.gov/regulation-supervision/cybersecurity-resources

- NIST SP 800‑218, Secure Software Development Framework (SSDF) v1.1. National Institute of Standards and Technology. https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-218.pdf

- NIST SP 800‑160 Volume 1, Systems Security Engineering. National Institute of Standards and Technology. https://nvlpubs.nist.gov/nistpubs/SpecialPublications/NIST.SP.800-160v1.pdf

- Cybersecurity Assessment Tool (CAT) – Sunset Statement (2024). Federal Financial Institutions Examination Council. https://www.ffiec.gov/resources/cat

- SR 21‑11: FFIEC Architecture, Infrastructure and Operations Examination Handbook. Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. https://www.federalreserve.gov/supervisionreg/srletters/SR2111.htm

- OCC Bulletin 2023‑22 – Cybersecurity Supervision Work Program. Office of the Comptroller of the Currency. https://www.occ.treas.gov/news-issuances/bulletins/2023/bulletin-2023-22.html

- NCUA 2025 Supervisory Priorities. National Credit Union Administration. https://ncua.gov/regulation-supervision/letters-credit-unions-other-guidance/ncuas-2025-supervisory-priorities

Table of Contents

Subscribe